Introduction

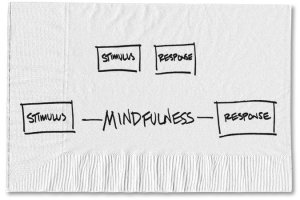

The Alexander Technique (AT) is a holistic educational method that helps individuals change inefficient or faulty habits, reducing potentially harmful stress (allostatic load) & tension accumulation. This is accomplished by observing and altering how one conceptualizes responses to stimuli with the aid of an AT teacher.

The AT is known to affect postural tone and movement coordination (Cacciatore et al., 2011; Preece et al., 2016); however, the AT is not a passive treatment (Williams, 2018). While movement is a focus in learning the AT, it is generally taught as an educational system rather than movement therapy (Woods, 2020). AT can also be described as a phenomenological study of the interaction between one’s biology and psychology (Mindbody). AT practice observes and modulates the relationship between volitional cognitive behavior, somatosensory awareness, and regulation of muscle activity in postural support and movement.

The most recent systematic review of AT trials is Woodman & Moore (2011) which identified AT in the treatment of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) associated disability and chronic back pain as promising areas of research. According to the Mayo Clinic, “Back pain is a leading cause of disability worldwide and its origins are often unclear.” Education is universally recommended as first-line treatment for acute and persistent back pain but it attracts little attention; the vast majority of back pain episodes do not require surgery or long-term powerful analgesics (Moseley, 2019).

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disease that includes a range of symptoms related to control of posture (Doherty et al., 2011). Medication sometimes alleviates some Parkinsonian motor symptoms, but it does not cure them and may make aspects of postural control worse (Contin et al., 1996). According to the National Health Service (UK), “lessons in the Alexander Technique may help one carry out everyday tasks more easily and improve feelings about Parkinson’s disability.” The primary symptoms of PD are muscular rigidity, slowness, tremor, and postural instability.

Studies of the AT on persons with PD disability and back pain illustrate the potential bio-psychological effects of cultivating interoceptive and proprioceptive awareness through AT lessons (Stallibrass et al., 2002; Little et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2015). Further evidence comes from a systematic review of a number of trials that found AT lessons improve performance anxiety in musicians (Klein et al., 2014).

The main hypothesis here is that the mechanisms of action and effects of the AT can be, at least partially, explained by known biological/cognitive mechanisms. However, explaining phenomena like back pain and improvements in it from mind-body practices is, in itself, problematic. While clinical research advocates using the biopsychosocial model (BPS) to manage back pain, there is still no clear consensus on the meaning of this model in physiotherapy and how best to apply it. Biological, psychological, and social factors may be inadequate to address complexities of people with back pain, and a reworking of the model may be necessary (Mescouto et al., 2022). A phenomenological approach may be needed in addition to the BPS to make sense of the meaning of the experience of back pain and/or the treatments for it (Stilwell & Harman, 2021).

History

The AT has been used for over 125 years in a wide variety of educational and medical settings, however, a comprehensive neurophysiological model theory of biological mechanisms of action underlying the AT’s effects has only recently been proposed by Cacciatore, Johnson, & Cohen (2020). Current theories, including this paper, rest heavily on the work of Dr. Timothy Cacciatore’s and Dr. Rajal Cohen’s rigorous research and numerous peer-reviewed publications about or related to the AT. The prior vagueness in the definitions of the AT originated from the complexity of underlying systems and generally unsophisticated techniques in describing psycho-physical activity/behavior. Improvements in the ability to observe and record psychomotor and brain behavior generally have made such a model viable only recently relative to the age of the AT. The situation was similar for many of the early psychotropic drugs that were discovered somewhat serendipitously with no clear explanation for their purported mechanisms of action (Carey et al., 2020).

Dr. David Garlick, a physiologist and medical research scientist at the University of New South Wales, laid the groundwork for current theories of AT mechanisms in the 1980s. He stressed that the awareness of inter-relationship of muscle and mental states (body schema) as one of the most important effects of the AT. Garlick’s research included various types of postural analysis, the majority of which were published in The Lost Sixth Sense (1990). The “sixth sense” in this context refers to underdevelopment and/or malfunctioning of kinesthetic and proprioceptive senses. Garlick postulated that the AT mainly operates on these senses and the brain mechanisms related to those senses. He lists sensory nerve inputs from neck muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, skin and joint receptors, and differences in types of muscle fibers as physiological factors relevant to the transmission and reception of psychomotor information used in dyadic AT practice (Garlick, 1990).

More information on early AT research can be found here.

The Mind-body Problem

The false dichotomy of physical and nonphysical, mind and body, pervades medicine and causes many problems in conceptualization of disease, particularly with regards to so-called ‘mental illness’ (Mehta, 2011). The reality that the mind has no existence other than as an abstract cultural relational tool escapes the majority of people to this day. This is hard to accept for followers (and cultural descendants) of Abrahamic religions that long equated mind (personality/psyche/ego) with atomistic souls living in the ether or spiritual realm and merely interacting with the physical body. Mind-body dualism is so pervasive culturally that atheists are not immune; most people subconsciously separate mind and body to some degree because of cultural conditioning.

Reductionism by contrast, in the strict sense envisioned by its creators in the 1930s, is largely impractical in biology and was effectively abandoned by the early 1970s. Classical holism was a stillborn theory (from Vitalism) of the 1920s and the term has survived in several fields as a loose umbrella designation for various kinds of anti-reductionism (Gatherer, 2010). The AT is one such anti-reductionist holistic practice.

Of course one’s ‘mind’ is ultimately physical, even as an abstract idea it must exist as some arrangement of neuronal pathways. Therefore, treatments such as talk therapy are not purely ‘non-physical’ as this would be ignoring the reality of what’s happening in the brain during such ‘non-physical’ treatments. There is some debate as to if talk therapy constitutes a medical treatment, but this sentiment itself likely stems from the problematic separating of physical and non-physical (‘mental’) outcomes and treatments as if they acted on seperate systems. Problems of interaction that arise from these categorizations seem to suggest a fundamental error in conception of the underlying systems.

Alexander Technique Method

AT teachers use skilled manual contact to observe and assess changes in activity, balance, and coordination. The teacher then highlights this behavior for the student while simultaneously giving verbal suggestions or directing the student’s use of volitional cognitive behavior (‘direction’ or conscious autosuggestion). With manual and verbal direction from the teacher, pupils learn to recognize and adopt better behavioral strategies. AT is particularly relevant in the interplay of cognition, behavior, and the initiation of movement (Stallibrass et al., 2002).

A core aspect of AT is a volitional cognitive behavior process called ‘directing,’ which involves applying specific intentions to postural tone, body schema, and spatial awareness. The practice of ‘directing’ attention to postural tone and body schema also involves monitoring departures from postural intentions and applying inhibitory control to motor planning to prevent automatic patterns of muscle activation, i.e. habits (Cacciatore et al., 2020).

‘Inhibiting,’ another core volitional cognitive behavior process in AT, may refer to the ‘undoing’ or prevention of unnecessary muscular activity, whether at rest, in anticipation, or in action. In an AT lesson, inhibition may also refer to prevention of motor planning while performing an action. The AT process of inhibiting may also refer to a more general intentional calming of the nervous system (Cacciatore et al., 2020). ‘Direction’ and ‘Inhibition’ as AT concepts may be two sides of the same coin rather than distinct ideas.

The functional organization and balance of the central body axis plays a primary role in AT because of the critical role of postural tone in this region. The neck may be especially crucial due to its proximal location at the top of spine and direct role in orienting the head (Loram et al., 2017). In one study, participants reported significantly reduced neck pain and fatigue of the superficial neck flexors during a cranio-cervical flexion test after AT lessons (Becker, 2018). In another study, patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain were given AT lessons or acupuncture and both added a small but clinically significant reduction in pain (MacPherson, 2015; Baime, 2016).

The spine’s instability and its central location require that axial tone mediate use of the limbs. Failure to dynamically adapt axial tone can manifest as jerky, uncomfortable, or poorly controlled movement (Gurfinkel et al., 2006). Correcting this can have wide-ranging benefits as postural tone interacts with executive processes, motor acts, emotional regulation, and pain (Cacciatore et al., 2011).

Taken together, ‘direction,’ ‘inhibition,’ and the prime importance of coordination and balance in the central body axis (torso/spine), form the basis of the theory of AT practice. The AT’s effects are theorized to come from positively affecting postural tone, which in turn has other cascading effects. Although the effectiveness of AT lessons has been shown at the behavioral level, their effects on altering brain circuitry are still unclear.

Similarities to MECPs and Psychotherapy

The AT has strong similarities with movement-based embodied cognitive practices (MECPs) such as Yoga (Schlinger, 2006), Qigong (Posadzki, 2009), and Tai Chi (Schmalzl, 2014); as well as more modern derivatives including variations on ‘mindfulness,’ (Siegel, 2007; Stern, 2021) like Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Anheyer, 2017). There are also correlations with various ‘somatic education/therapy’ methods (Kim, 2018).

The similarities include multiple parallels in effects treating back pain and PD disability between Yoga (Cramer et al., 2013; Ban et al., 2021) Tai chi (Li et al. 2012), and the Alexander Technique (Stallibrass, 2002; Little et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2015). This further suggests that mechanisms of action are likely shared among MECPs and AT. One can start to make educated guesses about AT and the brain from imaging studies of these related fields.

There are also many parallels with psychotherapy (Ashar et al., 2022). Dyadic or dialectical contemplation, typically master and pupil, is at the core of many Eastern mindfulness modalities and MECPs and is similar in Western systems such as the AT and body-oriented psychotherapy (Posadzki, 2009; Kim, 2018; Stern, 2021). Interestingly, the AT influenced some forms of psychotherapy, including Gestalt therapy (Tengwall, 1981). Xuan et al. (2020) is a good example of the effectiveness of some Eastern mindfulness practices infused Western therapy practices.

Within the field of contemplative science, the directing of attention to bodily sensations has so far mainly been studied in the context of seated meditation and mindfulness practices. Early cognitive research neglected the issues concerning the activation of action, preparedness, direction, and termination of action (Pervin, 1992). Advances in the neuroscience of motor control and promising initial results have led to increased interest in the role of cognition in motor behavior and the effect of body state on mental state. Fairly recently, cognitive neuroscience started to realize that mental functions cannot be fully understood without reference to the physical body and has shifted from a predominantly disembodied and computational view of the mind to embodied viewpoints (Schmalzl et al., 2014).

AT’s Relationship to Pain, Body Schema and Proprioception

A related component problem of pain is the emotional implications of chronic pain. Functional imaging studies have shown that stimuli associated with pain can activate the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) even when no actual painful stimulus is applied. Singer et al. (2004) found that when women received a painful electrical shock to the back of their hand, their ACC, anterior insular cortex, thalamus, and somatosensory cortex became active. When they saw their partners receive a painful shock but did not receive one themselves, the same regions (except for the somatosensory cortex) became active (Carlson & Brickett, 2022). This illustrates that at least some parts of pain are indeed, ‘in our heads.’ The emotional component of pain can be provoked by empathy for someone, causing responses in the brain like the ones caused by actual pain.

A particularly relevant form of chronic pain in this context is phantom limb pain as one theory maintains that phantom limb pain can arise from a conflict between visual feedback and proprioceptive feedback from the phantom limb (Carlson & Brickett, 2022). People with low back pain (LBP) have, on average, reduced lumbar range of movement and proprioception; they also move more slowly compared to people without LBP (Laird et al., 2014). Chronic back and hand pain are associated with deficits in body schema (Gilpin et al., 2015).

Proprioceptive musculoskeletal education (AT) was shown to enhance respiratory muscular function in normal adults (Austin, 1992) suggesting a connection between AT, proprioception, and muscle activity of the torso/abdomen. Another AT study potentially related to altered body schema showed improvements in functional reach after AT lessons in healthy older women (Dennis, 1999). After overview of the research, Cacciatore et al. (2020) proposed a comprehensive neurophysiological model of the AT suggesting that a primary mechanism of AT’s effects is improving deficits in body schema.

The largest AT study to date was a randomized controlled trial with 579 participants led by Dr. Paul Little (Little et al., 2008). The so-called “ATEAM” trial evaluated the economic viability of therapeutic massage, exercise, and lessons in the AT for treating chronic and recurrent back pain, comparing the costs and outcomes at 12 months of courses of 6 and 24 lessons in the AT, 6 sessions of massage, and a general practitioner’s prescription for home-based exercise with a nurse follow-up for patients with chronic or recurrent non-specific back pain in primary care.

Exercise and lessons in the AT, but not massage, remained effective at one year; 24 lessons had the best results (measured in recorded days with vs without pain), but six lessons followed by exercise prescription was ‘85% as effective’ as 24 lessons. Therefore, the combination of six AT lessons followed by exercise was found to be the most cost-effective option (Hollinghurst, 2008). AT was viewed as effective by most participants (Yardley et al., 2010) and authors suggest that the AT is a powerful tool for self-efficacy as participants were able to apply skills learned from lessons to continue independent learning in the 6 lessons plus exercise group (Little et al., 2008). Subsequent smaller randomized controlled trials have shown the results are repeatable (Hafezi et al., 2021). Considering parallel research, these results also suggest that AT may affect body schema.

Postural Tone and Motor Planning

To plan an action, the motor system integrates sensory information from different sources into a coherent model (Medendorp & Heed, 2019; Gurfinkel et al., 2006). Tone and body schema work together to govern postural organization and provide a foundation for movement and balance (Ivanenko & Gurfinkel, 2018; Cacciatore et al., 2020). In AT, spatial and body-schema phenomena are thought to be deeply interwoven with tone (Cacciatore et al., 2011). Changes in tone lead to changes in the perception of the structural organization of the body, and an improved body percept facilitates further improvements in tone (Loram, 2017).

Using EMG to record muscle activity, one study found AT lessons decreased axial stiffness by 29% on average in subjects with low back pain while resisting rotation, leading the authors to suggest that dynamic modulation of postural tone can be enhanced through long-term training in the AT (Cacciatore et al., 2011). As the research on AT and tone indicates, changes in distribution and adaptivity of tone affect movement and balance. In a broad sense, tone is a foundational system that affects other aspects of motor behavior.

Changes in tone from AT-based instructions suggest that executive function can influence tone and body schema (Cohen et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 2020). This process may be related to what movement scientists call kinesthetic motor imagery, although such studies mostly examine the mental representation of overt movement rather than mental representations of desired postural states (Cacciatore et al., 2020).

Changes in body schema could also underlie changes in the adaptivity of tone. Postural tone (possibly in interaction with body schema) forms the central thesis of the current theoretical model of the AT proposed by Cacciatore et al. (2020). Because body schema is used as a central reference for posture, movement planning, and execution; its accuracy, precision, and integration with the motor system are likely to have widespread motor effects. Postural tone and body schema are similar in that both concern neurophysiological states rather than sequential processes involved in actions (Gurfinkel et al., 2006), and both are particularly suited to influence motor behavior in general. While there is no direct evidence that AT changes body schema, innumerous observations from practitioners and students support its relevance to AT practice (Cacciatore et al., 2020).

Parallels in Developmental Coordination Disorder

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) has long been considered a motor disorder, but Martel and colleagues showed plasticity in body schema estimates used for motor control is altered in children and early adolescents with DCD, suggesting different pathology. The clinical assessment of the ability to point to or name several body-parts is generally preserved in children with DCD. This preserved motor learning, together with their noted reliance on vision to control hands and tools, point towards a body schema related deficit (Martel et al., 2022).

Children and early adolescents with DCD have trouble when comparing their predicted and received feedback, leading to difficulties in their body estimate (Pisella et al., 2019). Children with DCD experience difficulties in adjusting their body when their posture is challenged as this requires them to access their body representation for action. Physical therapists usually focus their approach on the body rather than motor disorders, working with children to improve their body awareness and find compensatory strategies (Martel et al., 2022). This sounds strikingly like the learning process in the AT and proposed mechanism of action by Cacciatore et al. (2020).

There have been no brain-imaging studies on AT treatment. However, clues into the brain mechanisms involved in AT lessons may be provided by related imagining research into Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). Symptoms of PD closely resemble symptoms of DCD and deficit in ‘body schema’ is hypothesized in both cases (Martel et al., 2022; Cacciatore et al., 2020).

‘Psychological’ Effects of AT

A variety of ‘non-physical’ outcomes of AT lessons including improved perceived general wellbeing and increased confidence were found by Kinsey et al. (2021). While physical effects of the AT are measurable, albeit subtle, non-physical outcomes are often reported and are difficult to quantify. Because AT practitioners and students philosophically conceive of the mind-body as an integrated whole, this interaction is not surprising (Tarr, 2011). Kinsey and colleagues make two informed theory statements on how non-physical outcomes can be generated by AT lessons: because the mind-body connection “improvements in physical wellbeing lead directly to psychological well-being,” and “an experience of mind-body integration leads people to apply AT skills to non-physical situations” (Kinsey et al., 2021).

Research that supports these theory statements can be found in the foundational work in AT & Parkinson’s (PD) done by Dr. Chloe Stallibrass and colleagues at the University of Westminster. A pilot study (Stallibrass, 1997) indicated that, in conjunction with drug therapy, AT could benefit people with PD. In a follow-up study (Stallibrass et al., 2002), ninety-three people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease were assigned into three groups (AT, massage, and no additional care) and assessed using the ‘Self-assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale’ (SPDDS), ‘Attitudes to Self-scale’ and ‘Beck Depression Inventory’ (BDI). An additional study (Stallibrass, 2005) investigated retention of skills from the main study by voluntary follow up self-assessment questionnaire responses. The AT group improved compared with the no additional intervention group, pre-intervention to post-intervention on SPDDS tests and was comparatively less depressed post-intervention, supporting evidence that lessons in the AT are likely to lead to sustained benefit for people with Parkinson’s disease and that AT lessons may have non-physical outcomes (Stallibrass et al., 2002).

A study of people with chronic lower back pain found significant differences before and after AT lessons in their constructs of intention, perceived risk, direct attitude, and behavioral beliefs providing more evidence of non-physical outcomes from AT lessons (Kamalikhah et al., 2016). Perhaps not coincidentally, the AT was influential in the creation of some forms of psychotherapy (Tengwall, 1981). Some speculate that these outcomes might be explained by the documented therapeutic qualities of empathic touch (Tarr, 2011; Jones & Glover, 2014).

‘Physical’ outcomes from Volitional Cognitive Behavior

There is also mounting evidence for psychophysical (physical and non-physical, Mindbody) outcomes among musicians applying the AT. A 2014 systematic review of trials found good evidence that AT lessons improve performance anxiety in musicians (Klein et al., 2014). A more recent a study found AT classes for music students may beneficially influence performance related pain, poor posture, excess muscle tension, stress, and performance anxiety (Davies, 2020). Another study of musicians reported that application of the AT to music performance showed improvements vs controls in heart rate variance, self-rated anxiety, and positive attitude to performance, as well as overall music and technical quality as judged by independent experts blind to subjects’ condition assignment (Valentine et al., 1995).

There have been multiple studies led by Dr. Rajal Cohen of the University of Idaho that quantitatively measured differences in axial tone, postural sway, postural uprightness, and step initiation; before and after verbal AT instruction among PD sufferers and healthy individuals (Cohen et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 2020). Improvements were recorded in the lateral center of pressure (CoP) displacement, smoothness of CoP path, axial rigidity (peak torque) and postural sway amplitude in both Parkinson’s patients and healthy individuals when given brief verbal instructions based on common AT directions compared to directions based on popular concepts of effortful posture correction (Cohen et al., 2015). These findings support other evidence that AT ‘thinking’ (direction, conscious autosuggestion, etc.) has distinct, measurable psychophysical outcomes.

Conclusion

Alexander recognized somatosensory defects, which he called ‘faulty sensory awareness’ and sometimes more provocatively ‘debauched kinesthesia’ as diseases of civilization as early as the 1890s. At the heart of most modern cognitive therapeutic modalities is the idea that maladaptive responses from our biology, that result in accumulation of chronic stress (allostatic load), can be cognitively inhibited to alter behavior and/or improve functioning.

Postural tone is a foundational system that affects all other aspects of motor behavior. The AT positively affects postural tone and therefore may indirectly positively affect all other aspects of motor behavior. Improvements in postural tone and body schema can, in turn, cause ‘non-physical’ outcomes because the interconnected nature of the mindbody denies the false dichotomy of physical and nonphysical. Taken together, these conclusions supports Alexander’s foundational assertion that ‘use’ (psychomotor behavior) affects the functioning of the human organism.

In light of the evidence presented, we can now make educated theory statements that were previously impossible about the questions like, “What is causing psychophysical change in AT practice and how does it happen?” The answer is most likely a combination of systems related to motor planning, interoception, proprioception, and empathic touch, that are recruited in the teaching/learning of the AT. With additional feedback from the instructor, the student’s interoception and proprioception is enhanced, causing modulation of body schema and postural tone. This enhanced state of awareness opens new possibilities for motor planning and behavior modification. Accumulation of enough experiences of enhanced interoception and proprioception develops the skill of recalling those states volitionally without a teacher.

The possible connections among body schema, postural tone, and motor control suggest an intriguing area of potential research on changes in body schema through AT instruction. Similarities between MECPs (Yoga, Tai chi, Qi gong, etc.), Somatic Education/Therapy, and Psychotherapy should be examined in a comparative study. In addition, these inquiries all have interesting implications for the philosophical mind-body problem.

References

Anheyer, D., Haller, H., Barth, J., Lauche, R., Dobos, G., & Cramer, H. (2017). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Treating Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine, 166(11), 799–807. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1997

Ashar, Y. K., Gordon, A., Schubiner, H., Uipi, C., Knight, K., Anderson, Z., Carlisle, J., Polisky, L., Geuter, S., Flood, T. F., Kragel, P. A., Dimidjian, S., Lumley, M. A., & Wager, T. D. (2022). Effect of Pain Reprocessing Therapy vs Placebo and Usual Care for Patients With Chronic Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 79(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2669

Austin, John H.M., and Pearl Ausubel. (1992) Enhanced respiratory muscular function in normal adults after lessons in proprioceptive musculoskeletal education without exercises. Chest, vol. 102, no. 2

Ban, M., Yue, X., Dou, P., & Zhang, P. (2021). The Effects of Yoga on Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Behavioural Neurology, 2021, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5582488

Baime, M. (2016). In chronic nonspecific neck pain, adding Alexander Technique lessons or acupuncture to usual care improved pain. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(6), JC29–JC29. https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-2016-164-6-029

Becker, Copeland, S. L., Botterbusch, E. L., & Cohen, R. G. (2018). Preliminary evidence for feasibility, efficacy, and mechanisms of Alexander technique group classes for chronic neck pain. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 39, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.05.012

Cacciatore, T. W., Johnson, P. M., & Cohen, R. G. (2020). Potential Mechanisms of the Alexander Technique: Toward a Comprehensive Neurophysiological Model, Kinesiology Review, 9(3), 199-213. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/krj/9/3/article-p199.xml

Cacciatore T., Mian O., Peters A., Day B. (2014) Neuromechanical interference of posture on movement: evidence from Alexander technique teachers rising from a chair Journal of Neurophysiology 2014 112:3, 719-729

Cacciatore T., Gurfinkel, V. S., Horak, F. B., Cordo, P. J., & Ames, K. E. (2011). Increased dynamic regulation of postural tone through Alexander Technique training. Human Movement Science, 30(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2010.10.002

Carey, T. A., Griffiths, R., Dixon, J. E., & Hines, S. (2020). Identifying Functional Mechanisms in Psychotherapy: A Scoping Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00291

Carlson, N., Birkett, M. (2022), Foundations of Behavioral Neuroscience (10th ed.) etext, Pearson

Contin M., Riva, R., Baruzzi, A., Albani, F., Macri’, S., & Martinelli, P. (1996). Postural stability in Parkinson’s disease: the effects of disease severity and acute levodopa dosing. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 2(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/1353-8020(95)00008-9

Cohen R., Gurfinkel, V. S., Kwak, E., Warden, A. C., & Horak, F. B. (2015). Lighten Up: Specific Postural Instructions Affect Axial Rigidity and Step Initiation in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 29(9), 878–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968315570323

Cohen, Baer, J. L., Ravichandra, R., Kral, D., McGowan, C., & Cacciatore, T. W. (2020). Lighten Up! Postural Instructions Affect Static and Dynamic Balance in Healthy Older Adults. Innovation in Aging, 4(2), igz056–igz056. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz056

Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(5) p.450-460 doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492

Davies, J. (2020) Alexander Technique classes improve pain and performance factors in tertiary music students Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies Vol. 24 Issue 1 p.1-7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.04.006

Debrabant, J., Vingerhoets, G., Van Waelvelde, H., Leemans, A., Taymans, T., & Caeyenberghs, K. (2016). Brain Connectomics of Visual-Motor Deficits in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. The Journal of pediatrics, 169, 21–7.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.069

Dennis Ronald J, (1999). Functional Reach Improvement in Normal Older Women After Alexander Technique Instruction, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Volume 54, Issue 1, Pages M8-M11 https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/54.1.M8

Doherty, K., van de Warrenburg, B. P., Peralta, M. C., Silveira-Moriyama, L., Azulay, J.-P., Gershanik, O. S., & Bloem, B. R. (2011). Postural deformities in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology, 10(6), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70067-9

Garlick D (1990). The Lost Sixth Sense: A Medical Scientist Looks at the Alexander Technique. STAT Books. ISBN 0733400019

Gatherer, D. So what do we really mean when we say that systems biology is holistic?. BMC Systems Biology 4, 22 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-4-22

Gurfinkel, V., Cacciatore, T.W., Cordo, P., Horak, F., Nutt, J., & Skoss, R.(2006). Postural muscle tone in the body axis of healthy humans. Journal of Neurophysiology, 96(5), 2678–2687. PubMed ID 6(5), 2678–2687. PubMed ID:16837660doi:10.1152/jn.00406.2006

Hafezi M., Rahemi Z., Ajorpaz N.M., Izadi F.S., (2021). The effect of the Alexander Technique on pain intensity in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Volume 29, Pages 54-59, ISSN 1360-8592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2021.09.025.

Hollinghurst S., Sharp, D., Ballard, K., Barnett, J., Beattie, A., Evans, M., Lewith, G., Middleton, K., Oxford, F., Webley, F., & Little, P. (2008). Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain: economic evaluation. British Medical Journal, 337(dec11 2), a2656–a2656. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2656

Ivanenko, Y., & Gurfinkel, V. S. (2018). Human postural control. Frontiers in Neuroscience, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00171

Jones, T. & Glover, L. (2014). Exploring the Psychological Processes Underlying Touch: Lessons from the Alexander Technique, Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 21, 140–153 DOI: 10.1002/cpp.1824

Kamalikhah T., Morowatisharifabad M. Rezaei-Moghaddam F., Ghasemi M. Gholami-Fesharaki M. Goklani S. (2016). Alexander Technique Training Coupled With an Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction in Teachers With Low Back Pain Iran Red Crescent Medical Journal 2016 Sep; 18(9): e31218. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.31218

Kim, S., (2018). Exploring the field application of combined cognitive-motor program with mild cognitive impairment elderly patients. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 14(5), 817–820. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.1836418.209

Kinsey D., Glover L., Wadephul F., (2021). How does the Alexander Technique lead to psychological and non-physical outcomes? A realist review, European Journal of Integrative Medicine, Volume 46, ISSN 1876-3820, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101371

Klein, S.; Bayard, C; Wolf, U (2014). “The Alexander Technique and musicians: a systematic review of controlled trials”. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 14: 414. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-414. PMC 4287507. PMID 25344325.

Li, F., Harmer, P., Fitzgerald, K., Eckstrom, E., Stock, R., Galver, J., Maddalozzo, G., & Batya, S. S. (2012). Tai Chi and Postural Stability in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(6), 511–519. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1107911

Little, P., Lewith, G., Webley, F., Evans, M., Beattie, A., Middleton, K., Barnett, J., Ballard, K., Oxford, F., Smith, P., Yardley, L., Hollinghurst, S., Sharp, D., & Van Tulder. (2008). Randomised Controlled Trial of Alexander Technique Lessons, Exercise, and Massage (ATEAM) for Chronic and Recurrent Back Pain. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 337(7667), 438–441. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20510639

Loram, I. D.,Bate, B., Harding, P., Cunningham R., Loram, A., (2017). Proactive Selective Inhibition Targeted at the Neck Muscles: This Proximal Constraint Facilitates Learning and Regulates Global Control, in IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 357-369, doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2016.2641024.

MacPherson H., Tilbrook, H., Richmond, S., Woodman, J., Ballard, K., Atkin, K., Bland, M., Eldred, J., Essex, H., Hewitt, C., Hopton, A., Keding, A., Lansdown, H., Parrott, S., Torgerson, D., Wenham, A., & Watt, I. (2015). Alexander Technique Lessons or Acupuncture Sessions for Persons With Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(9), 653–662. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0667

Martel, Boulenger, V., Koun, E., Finos, L., Farnè, A., & Roy, A. C. (2022). Body schema plasticity is altered in Developmental Coordination Disorder. Neuropsychologia, 166, 108136–108136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.108136

Mehta. (2011). Mind-body Dualism: A critique from a Health Perspective. Mens Sana Monographs, 9(1), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.77436

Moseley, G, L. (2019). Whole of community pain education for back pain. why does first-line care get almost no attention and what exactly are we waiting for? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(10), 588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099567

Pervin L. (1992). The Rational Mind and the Problem of Volition. Psychological Science, 3(3), 162–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00018.x

Pisella L., Havé L., Rossetti Y. (2019). Body awareness disorders: dissociations between body-related visual and somatosensory information Brain Volume 142, Issue 8, August 2019, Pages 2170–2173, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz187

Posadzki P. (2009). Qi Gong exercises through the lens of the Alexander Technique: A conceptual congruence. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 1(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2009.04.001

Preece, S.J., Jones, R.K., Brown, C.A. et al. (2016). Reductions in co-contraction following neuromuscular re-education in people with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 17, 372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1209-2

Sacks, Oliver (1985). The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales. Summit Books, Ch. 7 p. 67-72

Schlinger, Marcy (2006). Feldenkrais Method, Alexander Technique, and Yoga—Body Awareness Therapy in the Performing Arts Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics V.17,4 P865-875

Schmalzl, L., Crane-Godreau, M., & Payne, P. (2014). Movement-based embodied contemplative practices: Definitions and paradigms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00205

Siegel. (2007). Mindfulness training and neural integration: differentiation of distinct streams of awareness and the cultivation of well-being. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsm034

Stallibrass C. (1997). An evaluation of the Alexander Technique for the management of disability in Parkinson’s disease- a preliminary study. Clinical Rehabilitation.;11(1):8-12. doi:10.1177/026921559701100103

Stallibrass, C., Sissons, P., & Chalmers, C. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of the alexander technique for idiopathic parkinson’s disease. Clinical Rehabilitation, 16(7), 695-708. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215502cr544oa

Stallibrass, C., Frank, C., & Wentworth, K. (2005). Retention of skills learnt in Alexander technique lessons: 28 people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 9(2), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2004.06.004

Stern J. (2021). The Alexander Technique: Mindfulness in Movement Relieves Suffering Alternative and Complementary Therapies Volume: 27 Issue 1: February 11, 10-13. http://doi.org/10.1089/act.2020.29307.jcs

Stilwell, P., & Harman, K. (2021). Phenomenological Research Needs to be Renewed: Time to Integrate Enactivism as a Flexible Resource. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921995299

Tarr, Jennifer (2011). Educating with the hands: working on the body/self in Alexander Technique Sociology of Health & Illness Vol. 33 No. 2 ISSN 0141–9889, pp. 252–265doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01283.x

Tengwall, Roger (1981). A note on the influence of F. M. Alexander on the development of gestalt therapy Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences volume 17 issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696(198101)17:1<126::AID-JHBS2300170113>3.0.CO;2-X

Woodman, J. P. Moore, N. R. (2011). Evidence for the effectiveness of Alexander Technique lessons in medical and health-related conditions: a systematic review – International Journal of Clinical Practice VL – 66 IS – 1 SN – 1368-5031 UR https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02817.x

Yardley L., Dennison L., Coker R., Webley F., Middleton K., Barnett J., Beattie A., Evans M., Smith P., Little P., (2010). Patients’ views of receiving lessons in the Alexander Technique and an exercise prescription for managing back pain in the ATEAM trial, Family Practice, Volume 27, Issue 2, Pages 198–204, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp093

Valentine, E. R., Fitzgerald, D. F. P., Gorton, T. L., Hudson, J. A., & Symonds, E. R. C. (1995). The Effect of Lessons in the Alexander Technique on Music Performance in High and Low Stress Situations. Psychology of Music, 23(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735695232002

Xuan, R., Li, X., Qiao, Y., Guo, Q., Liu, X., Deng, W., Hu, Q., Wang, K., & Zhang, L. (2020). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113116–113116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113116

Websites:

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alexander-technique/

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/back-pain/symptoms-causes/syc-20369906

The primary directions, or preventative orders as Alexander sometimes called them, are deceptively simple and can be painfully misleading at times. For years I would think to myself something like, “Allow the neck to be free to let the head go forward and up to allow the back to lengthen and widen to let the knees go forward and away” without any idea what those words meant. My AT teachers told me to “think” the directions, so I repeated those words to myself with little effect to the point where I wondered if there was any value in thinking the directions. Eventually I started to actively investigate for myself what those words meant and what I was actually doing when I was “thinking the directions.”

The primary directions, or preventative orders as Alexander sometimes called them, are deceptively simple and can be painfully misleading at times. For years I would think to myself something like, “Allow the neck to be free to let the head go forward and up to allow the back to lengthen and widen to let the knees go forward and away” without any idea what those words meant. My AT teachers told me to “think” the directions, so I repeated those words to myself with little effect to the point where I wondered if there was any value in thinking the directions. Eventually I started to actively investigate for myself what those words meant and what I was actually doing when I was “thinking the directions.”

This is perhaps the most confusing of the directions, as the word “put” seems to imply that “head forward and up” is a position of the head. Adding “in relation to the neck” (Head forward and up in relation to the neck), brings some clarity but still can be misleading because of the temptation to hold the head in a place one has deemed forward and up in relation to the neck.

This is perhaps the most confusing of the directions, as the word “put” seems to imply that “head forward and up” is a position of the head. Adding “in relation to the neck” (Head forward and up in relation to the neck), brings some clarity but still can be misleading because of the temptation to hold the head in a place one has deemed forward and up in relation to the neck. “What’s up?” you might ask. The deep muscles that run along the spine provide a natural upward flow that opposes gravity. These deep muscles are made up of special fibers that are much more resilient in the face of the constant force of gravity than our superficial musculature. The skull was designed to be poised atop the upward flow of the spine. Balancing the head on top of the spine is similar to balancing a ball on top of a column of air. The major difference being that the head can’t completely fall off because we’ve got muscles and ligaments keeping it attached.

“What’s up?” you might ask. The deep muscles that run along the spine provide a natural upward flow that opposes gravity. These deep muscles are made up of special fibers that are much more resilient in the face of the constant force of gravity than our superficial musculature. The skull was designed to be poised atop the upward flow of the spine. Balancing the head on top of the spine is similar to balancing a ball on top of a column of air. The major difference being that the head can’t completely fall off because we’ve got muscles and ligaments keeping it attached. Lengthening comes from allowing the force of gravity to move through the bodies of the vertebra (front of the spine) so the deep spinal muscles, which are not under conscious control, can react in kind. When we interfere by holding ourselves upright (most people’s conception of sitting or standing up straight) we are shifting the workload from muscles that were designed to support the skeleton for long periods in gravity to muscles that were designed to lift heavy objects or strike a death blow to an animal (activities that require short bursts of great power).

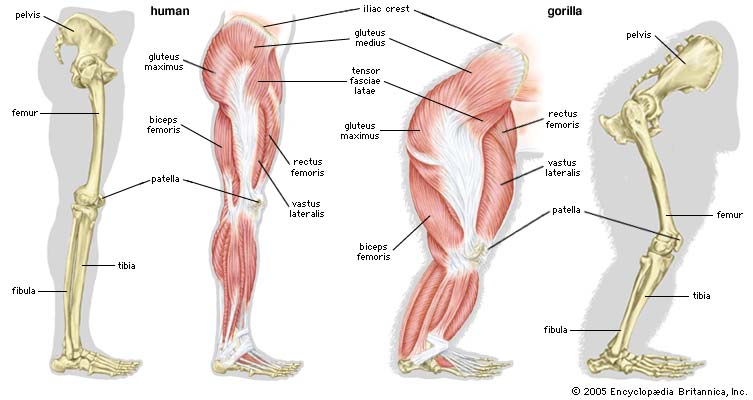

Lengthening comes from allowing the force of gravity to move through the bodies of the vertebra (front of the spine) so the deep spinal muscles, which are not under conscious control, can react in kind. When we interfere by holding ourselves upright (most people’s conception of sitting or standing up straight) we are shifting the workload from muscles that were designed to support the skeleton for long periods in gravity to muscles that were designed to lift heavy objects or strike a death blow to an animal (activities that require short bursts of great power). It is important to understand that our limbs come out of our backs. It’s easier to see in our similar the gorilla (right), but we still have the same basic set-up. Thinking of our gluteus maximus (glutes as they are commonly known) originating from the sides of the sacrum (roughly under the buttocks) and then out from the sacrum and lengthening down the backs and sides of the legs is essential to sending the knees forward and away from the pelvis. Another way of saying knees forward and away is: knees not pulled backward and up into the hip joints.

It is important to understand that our limbs come out of our backs. It’s easier to see in our similar the gorilla (right), but we still have the same basic set-up. Thinking of our gluteus maximus (glutes as they are commonly known) originating from the sides of the sacrum (roughly under the buttocks) and then out from the sacrum and lengthening down the backs and sides of the legs is essential to sending the knees forward and away from the pelvis. Another way of saying knees forward and away is: knees not pulled backward and up into the hip joints. When you think knees forward and away from heels directed back and down away from your lengthening and widening torso that is directed back and up in relation to the head that’s directed forward and up; you’ve got the whole thing and could go round starting anywhere. Because of the limitations of language, we can’t say or verbally think all of that at once, but we can think the kinesthetic meaning of those words all at once when we have some idea of what they mean. Alexander would often say, “All together and one at a time.”

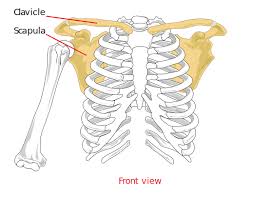

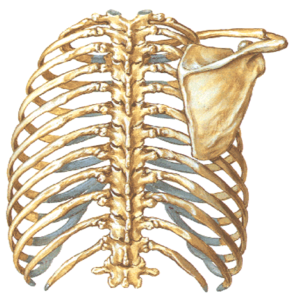

When you think knees forward and away from heels directed back and down away from your lengthening and widening torso that is directed back and up in relation to the head that’s directed forward and up; you’ve got the whole thing and could go round starting anywhere. Because of the limitations of language, we can’t say or verbally think all of that at once, but we can think the kinesthetic meaning of those words all at once when we have some idea of what they mean. Alexander would often say, “All together and one at a time.” Let’s begin with the basic anatomy of the shoulder girdle. When I refer to the “shoulder girdle” I mean the hands & arms, shoulder blades, and collar bone. You may be surprised to learn that the only jointed (bone to bone) connection of the shoulder girdle to the rest of the skeleton is in the front of the torso at the top of the sternum.

Let’s begin with the basic anatomy of the shoulder girdle. When I refer to the “shoulder girdle” I mean the hands & arms, shoulder blades, and collar bone. You may be surprised to learn that the only jointed (bone to bone) connection of the shoulder girdle to the rest of the skeleton is in the front of the torso at the top of the sternum.

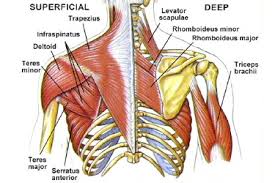

Now, palpate your way back to toward the mid-line from the acromion, this time following the shoulder blade until it reaches what will feel like the corner of a triangle. You are feeling the “spine” of the scapula. Depending on your muscle build you may have to press quite firmly and the scapula may seemingly disappear into muscle. The strong muscles of the back are what support and stabilize the shoulder girdle as there are no bone to bone attachments in the back. The structure of the shoulder girdle, while providing extreme freedom of movement, also brings an ambiguousness when looking for a neutral position for the shoulders and arms.

Now, palpate your way back to toward the mid-line from the acromion, this time following the shoulder blade until it reaches what will feel like the corner of a triangle. You are feeling the “spine” of the scapula. Depending on your muscle build you may have to press quite firmly and the scapula may seemingly disappear into muscle. The strong muscles of the back are what support and stabilize the shoulder girdle as there are no bone to bone attachments in the back. The structure of the shoulder girdle, while providing extreme freedom of movement, also brings an ambiguousness when looking for a neutral position for the shoulders and arms. It shouldn’t be a surprise that how we use ourselves in our daily activities has a profound effect on the resting lengths of our muscles. It is this phenomenon that we are observing when we see pianists and people who spend hours at the computer still in the shape they work from when walking, eating, watching TV, etc. In the case of the shoulder girdle this can be quite extreme. Because of the lack of bony structural support, the resting position of our shoulders is almost completely determined by the resting lengths of our muscles. If we overstretch our muscles in daily activity, we run the risk of deteriorating the support that allows the shoulders to find a comfortable resting position.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that how we use ourselves in our daily activities has a profound effect on the resting lengths of our muscles. It is this phenomenon that we are observing when we see pianists and people who spend hours at the computer still in the shape they work from when walking, eating, watching TV, etc. In the case of the shoulder girdle this can be quite extreme. Because of the lack of bony structural support, the resting position of our shoulders is almost completely determined by the resting lengths of our muscles. If we overstretch our muscles in daily activity, we run the risk of deteriorating the support that allows the shoulders to find a comfortable resting position.

As musicians we tend to segregate our practice time. We reserve time specifically for scales, run-throughs, and “technique,” among other things. The aspect of technique was always my primary interest. I would easily bore of concertos and sonatas, often before getting them up to a performance level, but I could practice the same passage focusing on improving my technique endlessly without boredom if it offered the kinds of challenges I needed to grow. I found that improvements that came from this type of practice had an overall improvement on my playing no matter if I was sight-reading or playing the passage I had been practicing.

As musicians we tend to segregate our practice time. We reserve time specifically for scales, run-throughs, and “technique,” among other things. The aspect of technique was always my primary interest. I would easily bore of concertos and sonatas, often before getting them up to a performance level, but I could practice the same passage focusing on improving my technique endlessly without boredom if it offered the kinds of challenges I needed to grow. I found that improvements that came from this type of practice had an overall improvement on my playing no matter if I was sight-reading or playing the passage I had been practicing. The viola is an inanimate object after all, so what we call viola technique can’t be separated realistically from the technique of movement while balancing in gravity. We are moving around the viola, supporting it, and manipulating it. The viola can only respond to what we do. Suddenly my experience of the AT applied to the viola got vastly clearer and I realized what an idiot I had been for separating the two skills in my mind. I realized that by narrowly focusing on my fingers and arms I drew myself closer to the viola seemingly in an attempt to bring my self (brain, spine, heart, consciousness) closer to the activity.

The viola is an inanimate object after all, so what we call viola technique can’t be separated realistically from the technique of movement while balancing in gravity. We are moving around the viola, supporting it, and manipulating it. The viola can only respond to what we do. Suddenly my experience of the AT applied to the viola got vastly clearer and I realized what an idiot I had been for separating the two skills in my mind. I realized that by narrowly focusing on my fingers and arms I drew myself closer to the viola seemingly in an attempt to bring my self (brain, spine, heart, consciousness) closer to the activity.

The Alexander Technique by Judith Leibowitz & Bill Connington opens, not with a technical definition or theoretical/philosophical description as many books on the Alexander technique do, instead the authors choose to begin with a relatable list of a variety of imaginary people with stress related ailments asking the reader what they have in common followed by a very straightforward explanation that excess tension and stress are direct results of misuse of the body. They even go so far as to list a number of conditions that can be alleviated by using the Alexander Technique.

The Alexander Technique by Judith Leibowitz & Bill Connington opens, not with a technical definition or theoretical/philosophical description as many books on the Alexander technique do, instead the authors choose to begin with a relatable list of a variety of imaginary people with stress related ailments asking the reader what they have in common followed by a very straightforward explanation that excess tension and stress are direct results of misuse of the body. They even go so far as to list a number of conditions that can be alleviated by using the Alexander Technique.

Body Learning by Michael J. Gelb was one of the first texts I read on the Alexander Technique, as it was required reading in the very first group introduction to the AT class I took. Upon re-reading it I see now why my teacher and so many others recommend the book to people with little or no experience with the AT. The book contains all of the core concepts of the Alexander Technique with minimal pontificating on possibilities of the future of mankind and other dense topics that plague many AT books, including ones written to be introductions. Also somewhat important in an introduction to the Alexander technique, which can sometimes be seen as a strange and esoteric practice, is the fact that Michael Gelb carriers some weight as an author from his other books which lends itself to the AT; not to mention the many endorsements by well-known individuals in related fields and a foreword by Walter Carrington.

Body Learning by Michael J. Gelb was one of the first texts I read on the Alexander Technique, as it was required reading in the very first group introduction to the AT class I took. Upon re-reading it I see now why my teacher and so many others recommend the book to people with little or no experience with the AT. The book contains all of the core concepts of the Alexander Technique with minimal pontificating on possibilities of the future of mankind and other dense topics that plague many AT books, including ones written to be introductions. Also somewhat important in an introduction to the Alexander technique, which can sometimes be seen as a strange and esoteric practice, is the fact that Michael Gelb carriers some weight as an author from his other books which lends itself to the AT; not to mention the many endorsements by well-known individuals in related fields and a foreword by Walter Carrington.

Having had a fair amount of personal experience with John Nicholls in lessons and classes, I had some preconceived ideas about how this book would read. I expected a straight-forward pseudo-medical explanation with scientific research to support the ideas without the “hippie stuff” that comes with many of his generation’s group of teachers. I was surprised that within the first chapter the conversation had already included Buddhist meditation, Gurdjieff, and possibilities for world change as a result of AT work. The subject of morality came up as John Dewey, Dr. Frank Pierce Jones, and Aldous Huxley believed that the technique lead to a form of ethics/morality. John Nicholls inferred that, “[the AT] may help the construction of a personal morality out of one’s own experience;” that the AT helps “to connect with the inner guide.” JN drew connections through many seemingly unrelated areas; he pointed out an interesting parallel to the schooling of horses, noting that the idea of “Self-carriage” or support of the limbs by the back is very similar to the idea of Primary Control. All of the subjects were approached and discussed in very practical ways without making any far reaching claims lacking evidence.

Having had a fair amount of personal experience with John Nicholls in lessons and classes, I had some preconceived ideas about how this book would read. I expected a straight-forward pseudo-medical explanation with scientific research to support the ideas without the “hippie stuff” that comes with many of his generation’s group of teachers. I was surprised that within the first chapter the conversation had already included Buddhist meditation, Gurdjieff, and possibilities for world change as a result of AT work. The subject of morality came up as John Dewey, Dr. Frank Pierce Jones, and Aldous Huxley believed that the technique lead to a form of ethics/morality. John Nicholls inferred that, “[the AT] may help the construction of a personal morality out of one’s own experience;” that the AT helps “to connect with the inner guide.” JN drew connections through many seemingly unrelated areas; he pointed out an interesting parallel to the schooling of horses, noting that the idea of “Self-carriage” or support of the limbs by the back is very similar to the idea of Primary Control. All of the subjects were approached and discussed in very practical ways without making any far reaching claims lacking evidence. The Alexander Technique As I See It by Patrick Macdonald is a charming, clear, and at times laugh out loud funny take on learning, teaching, and practicing the Alexander Technique.

The Alexander Technique As I See It by Patrick Macdonald is a charming, clear, and at times laugh out loud funny take on learning, teaching, and practicing the Alexander Technique.

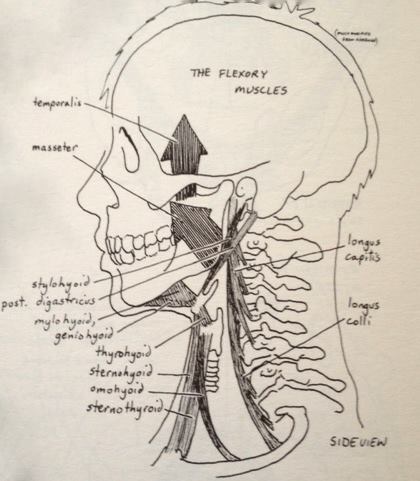

Freeing the neck is an undoing of holding, pushing, and pulling on the neck by the various neck muscles. You can’t do an undoing, so to allow the neck to be free you are gently asking the muscles of the neck, especially those under the back of the skull, to release into length.

Freeing the neck is an undoing of holding, pushing, and pulling on the neck by the various neck muscles. You can’t do an undoing, so to allow the neck to be free you are gently asking the muscles of the neck, especially those under the back of the skull, to release into length. This is perhaps the most confusing of the preventive orders as the word “put” seems to imply that “head forward and up” is a position of the head. Adding: in relation to the neck brings some clarity but still can be misleading because of the temptation to hold the head in a place one has deemed forward and up in relation to the neck.

This is perhaps the most confusing of the preventive orders as the word “put” seems to imply that “head forward and up” is a position of the head. Adding: in relation to the neck brings some clarity but still can be misleading because of the temptation to hold the head in a place one has deemed forward and up in relation to the neck.

Lengthening comes from allowing the force of gravity to move through the bodies of the vertebra (front of the spine) so the deep spinal muscles, which are not under conscious control, can react in kind. When we interfere by holding ourselves upright (most people’s conception of sitting or standing up straight) we are shifting the workload from muscles that were designed to support the skeleton for long periods in gravity to muscles that were designed to lift heavy objects or strike a death blow to an animal (activities that require short bursts of great power).

Lengthening comes from allowing the force of gravity to move through the bodies of the vertebra (front of the spine) so the deep spinal muscles, which are not under conscious control, can react in kind. When we interfere by holding ourselves upright (most people’s conception of sitting or standing up straight) we are shifting the workload from muscles that were designed to support the skeleton for long periods in gravity to muscles that were designed to lift heavy objects or strike a death blow to an animal (activities that require short bursts of great power). It is important to understand that our limbs come out of our backs. It’s easier to see in our similar the gorilla (right), but we still have the same basic set-up. Thinking of our gluteus maximus (glutes as they are commonly known) originating from the sides of the sacrum (roughly under the buttocks) and then out from the sacrum and lengthening down the backs and sides of the legs is essential to sending the knees forward and away from the pelvis. Another way of saying knees forward and away is: knees not pulled backward and up into the hip joints.

It is important to understand that our limbs come out of our backs. It’s easier to see in our similar the gorilla (right), but we still have the same basic set-up. Thinking of our gluteus maximus (glutes as they are commonly known) originating from the sides of the sacrum (roughly under the buttocks) and then out from the sacrum and lengthening down the backs and sides of the legs is essential to sending the knees forward and away from the pelvis. Another way of saying knees forward and away is: knees not pulled backward and up into the hip joints.