There have been several articles in the New York times on mindfulness recently and it would seem that mindfulness is back in vogue. One that caught my eye most recently was focused on a study that found that pausing, even for just half a second, between having a thought and making a decision to act on that thought improved decision making.

There have been several articles in the New York times on mindfulness recently and it would seem that mindfulness is back in vogue. One that caught my eye most recently was focused on a study that found that pausing, even for just half a second, between having a thought and making a decision to act on that thought improved decision making.

Now this isn’t shocking new information to many people, especially anyone who has studied the Alexander Technique; but the question, “How do we access the space between thought and action?” is still an interesting one.

Most mindfulness practices when boiled down to their essence consist of these instructions:

- Be conscious of what you’re doing while you’re doing it. Pay attention without judgement to the present moment, not letting your mind wander elsewhere.

- Include your self doing the activity in your awareness, don’t solely focus on what you’re doing.

- When you notice your mind wandering, bring your attention to your breathing/feelings.

There are many variations and exercises designed to cultivate this state of ‘mindfulness’ but they are all essentially related to the above. The principles seem simple enough but try putting them into practice. You will soon find that it’s difficult to notice your mind wandering and come back to the awareness of your breath when you’re doing nothing, let alone when there is a task at hand.

Here’s where the Alexander Technique is invaluable. Through hands on experiences from a teacher your awareness of your self is significantly improved so it doesn’t require so much effort to pay attention to what you’re doing.

Most people have difficulty being conscious of what they are doing because there is a general misunderstanding of the nature of consciousness. Consciousness is not the voice in your head as many of us believe; however, we can be conscious of the voice in our head. Consciousness is also not our brains telling our bodies what to do non-verbally (i.e. desire for coffee, lift right arm to pick up coffee). We can be conscious and experience these things, but for the most part we are watching our unconscious habits unfolding. This is different than making a conscious decision. Consciousness essentially allows us to do two things. Pick a direction and stop; although not necessarily in that order. Generally you must stop doing your habit(s) that are taking you in directions you don’t want to be going to move in a direction you do want to go.

The difficulty here is that we have so many unconscious habits going on below the level of our awareness and it’s nearly impossible to stop doing something we don’t know we’re doing.

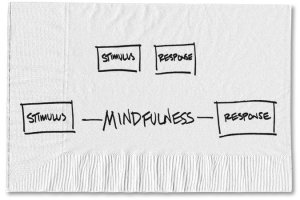

One thing I never liked about the word mindfulness is that it implies a separation between the mind, body, and consciousness. The three are parts of a whole that are intimately connected and functionally equivalent. The nervous system takes in sensory information and responds to the various stimuli we encounter. Our consciousness is able to access a limited amount of that information at any given time in order to act as a failsafe to our instinctual reactions. If the wrong response is learned one can inhibit the reaction by being conscious (or mindful if you will) and creating a space between stimulus and response for choice.

F.M. Alexander discovered that the information registered by the nervous system could be distorted by patterns of malcoordination and muscular rigidity that originated in the conceptualization of movement and posture. This is a huge point to consider because if our sensory information is flawed, even if we make the space for choice our decision is based on unreliable sources. Therefore, proper use of the self which results in reliable sensory feedback is an essential first step to a successful mindfulness practice.

There are some things often taught as mindfulness that actually take you away from being consciously aware.

- Close your eyes when you pay attention to your breath.

Closing your eyes doesn’t bring you into the moment, it’s essentially hiding from it. You can’t very well take a moment to close your eyes to pay attention to your breath while driving on the freeway.

- Imagine a sunny day (or some other scenario that is pleasant).

Again this type of instruction takes your consciousness away from your self. It’s much more helpful to be aware of what is there and your reaction to it. Whatever is there will still be there when you come back from your happy place.

AT-Mindfulness Tips:

- Find the top of the spine (roughly between your ears/behind your eyes). See if you can keep your awareness of the top of your spine without losing your other senses; keep seeing, hearing, feeling your feet on the ground etc. This will expand and quicken your conscious awareness as you learn not to hyper-focus on one thing at the cost of everything else in your awareness.

- Seeing is a great indicator of the quality of your consciousness in any given moment. If your vision goes blurry, your presence has a similar quality. When you think about something, do you still see? Or do you turn your eyes toward your brain to concentrate? Is it necessary to leave the present moment to think?

- When you have the urge to do something (pick up your phone when it rings, cross the street on green, etc.), take a second to stop and find the top of your spine. Keep the awareness of the top of your spine as you give consent to the activity or choose to do something else. Notice if you are reacting or actually making a choice.

This is a great post and you’ve perfectly put into words the problems I’ve experienced with so-called “Mindfulness”. As an Alexander teacher I’ve also recently come across something called “Mental Training”, which again implies this separation between mind and body.