William Primrose is universally known as the virtuoso violist. In this article I explain through the lenses of the Alexander Technique what allowed him to reach his full potential and how everyone has this inborn potential.

Primrose is universally known as the virtuoso violist. In this article I explain through the lenses of the Alexander Technique what allowed him to reach his full potential and how everyone has this inborn potential.

It is obvious, even to the untrained eye, that Mr. Primrose had excellent use of himself. You need not venture beyond one of his video recordings of the Paganini Caprices for proof of this. The virtuoso violinist Mischa Elman is said to have exclaimed upon seeing his performance, “It must be easier on viola!” (the opposite is true of course). What gave Mr. Primrose this exceptional ability to stay easeful while playing the most difficult passages? His response to a question about practicing from the interview with David Dalton (Playing the Viola) provides some insight, “Now, there are students many years younger than I, who practice this etude sedulously, and their hand is never terribly facile. But we must remember that to an extent, dexterity lies in an inherent muscular and nervous system.” This is strikingly similar to what Patrick Macdonald, one of the first teachers trained by Alexander, had to say about exercises, “Exercises, particularly those calculated to bring about relaxation, will, in nearly every case, exaggerate the unwanted condition. Only those whose use of their bodies is extremely good can do exercises with impunity. The reason for this is that exercises make no fundamental change, they only promote what is already there, and if what is already there is bad, it is folly to accentuate it.”

Mr. Primrose was a natural, not just with regards to the viola- but in his everyday life. He never lost his childlike poise, even in the face of great challenge. Janos Starker (virtuoso cellist) described him as, “a man of enormous courage, humility, knowledge, and insatiable curiosity … a man reaching heights but never losing sight of his frailties, while unflinchingly pursuing the loftiest goals.” Those attributes are paramount to successful study and application of the Alexander Technique. F. M. Alexander described what he called the ‘right mental attitude’ as one of a curious child engaged in learning, par for the course for Mr. Primrose.

Mr. Primrose was a natural, not just with regards to the viola- but in his everyday life. He never lost his childlike poise, even in the face of great challenge. Janos Starker (virtuoso cellist) described him as, “a man of enormous courage, humility, knowledge, and insatiable curiosity … a man reaching heights but never losing sight of his frailties, while unflinchingly pursuing the loftiest goals.” Those attributes are paramount to successful study and application of the Alexander Technique. F. M. Alexander described what he called the ‘right mental attitude’ as one of a curious child engaged in learning, par for the course for Mr. Primrose.

You might be thinking, “I’m no natural, how could I ever hope to play like Primrose?” What Alexander discovered is that it is natural to use ourselves well, but for most people it is not habitual. We all have the potential to use ourselves (and in fact play the viola) as Primrose did, but we must learn to not do what takes us out of this natural state of being. Another way of saying this would be that rather than trying to directly do what he did, we must first not do what he didn’t do. There would be no way for someone to play like Mr. Primrose if he were actively pulling his head and limbs into his torso and shorting his stature; which brings us to Mr. Alexander’s discovery of an organizing principle of coordination of the self, what he called the ‘Primary Control.’

Alexander described the ‘Primary Control’ as “A certain relationship of the head, neck, and back.” It is not a position, but a dynamic relationship of a lengthening spine with the skull balanced delicately at the top and the ribs free to move with the breath. Alexander discovered that the organization of the Primary Control profoundly affects the quality of general use of the whole self. If the Primary Control is well organized, the general coordination of the self trends toward integration and organization, whereas if the Primary Control is not in a healthy relationship there is a tendency toward mal-coordination and disintegration. The Primary Control does not operate in a vacuum, as use of other parts affect it and the whole, but as the area in question contains the majority of our nervous system and is the central axis of support for balance and movement its role to play is both basic and of the utmost importance. If the habitual use of the Primary Control includes mal-coordination and disintegration it will manifest in the specific parts and in the activities of life which depend on the use of the self (everything). Put simply, use affects functioning.

A free-spirited young violinist named Karen Tuttle was so taken by Mr. Primrose’s ease of playing after seeing him perform with the London String Quartet in Los Angeles, that she immediately asked to study with him. He agreed on the conditions that she move to the East-coast to study at Curtis and that she switch from violin to viola. Ms. Tuttle is quoted from the interview ‘Body and Soul, “But because [he was so natural], trying to elicit information from him about something he did technically was a bit like asking the average person, ‘How do you breathe?’ Still I knew that I would be able to unravel my own technical problems by watching Primrose and absorbing what he did. Watching him was a great lesson in itself.” Ms.Tuttle eventually became his teaching assistant and Mr. Primrose would often refer students to her for technical questions claiming that she knew more about his playing than he did himself.

Ms. Tuttle began to notice that Primrose had what she called ‘releases’ before events in playing such as shifts, crescendi, changing the direction of the bow, etc; most noticeably in the neck and lower back/pelvic region. In other words, she was noticing that Mr. Primrose’s ‘Primary Control’ was becoming more organized and available in preparation for a movement/activity. What’s more, the release and subsequent movement continued through the gesture. She eventually developed a system of playing that she called ‘coordination’ in which she strived to integrate musical ideas, appropriate ‘releases’ in the body, and emotions with the ultimate goal of bringing as much of her self into the picture while playing the viola as possible (as Primrose did naturally).

While her discoveries were groundbreaking, very few of her students could grasp what she was on to. A likely culprit is the word, “release.” The true meaning of what she called ‘releases’ has little to do with physical gestures and superficial positions/movements. What she called release had to do with the initiation of the movement, however the movement itself was expansive and active, not collapsing and floppy. What she called release movements, are akin to what Alexander called lengthening and widening. The external movements involved in Tuttle coordination will happen naturally in someone who uses herself well, there is no need to consciously and artificially impose them.

Without the underlying natural use, the movements that are involved in Tuttle’s coordination are not very helpful. Tuttle had this to say about her use of the word release, “Release movements are predominantly subtle, have a soft yielding quality and, in those players inherently capable of them, they appear smooth and natural rather than extraneous or self-conscious … release is actually what initiates the movement.” In other words, natural movement starts with an undoing, because of this the movements involved in coordination can’t be done in the way most people understand doing. You can’t do an undoing after all.

We do not come into this world with an instruction manual when we are born, and our general use patterns are developed before we are terribly self aware. How we learn to balance, move, and think as children becomes our habitual use in everything we do later in life. As children, we learned intuitively and the self was a relatively blank canvas. We must remember that the self works as a whole and it is impossible to separate the mind, body, spirit. When we perform a specific task such as playing the viola, everything we know about balance, beauty, and indeed all of our personal experiences are in play as those experiences have been fed into our nervous system and have become integrated into the self.

We do not come into this world with an instruction manual when we are born, and our general use patterns are developed before we are terribly self aware. How we learn to balance, move, and think as children becomes our habitual use in everything we do later in life. As children, we learned intuitively and the self was a relatively blank canvas. We must remember that the self works as a whole and it is impossible to separate the mind, body, spirit. When we perform a specific task such as playing the viola, everything we know about balance, beauty, and indeed all of our personal experiences are in play as those experiences have been fed into our nervous system and have become integrated into the self.

If those experiences have had an effect of disintegrating of the self there will be general mal-coordination that manifests in everything we do. This is not to say that there is some rule that having pleasant experiences will produce good use or that bad experiences will produce bad use. It is how we react that counts. Most people believe that they are a slave to their experiences, “I’m like this because my horrible childhood.” Primrose states, “The student of whom I am very suspicious from the outset is the person who comes and presents me with a long list of teachers with whom he has studied … students who are always seeking the magic potion or are looking for greener pastures when the cure really lies within themselves.”

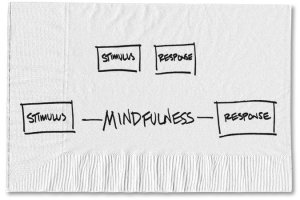

There are far too many reasons as to why our natural use is disrupted to spend much time on the topic in this context, but generally if we learn to respond to the various stimuli of life with fear, anxiety, and overworking, a specific activity will be experienced as scary, stressful, and difficult. If we meet the stimuli of life with curiosity, freedom, and expansiveness, the activity will be perceived as enlivening, interesting, and relatively easeful; regardless of the specific activity. This provides an explanation for the many accounts of individuals overcoming great hardship while remaining relatively unscathed, and similarly people for whom the smallest inconvenience is reacted to and experienced as the greatest hardship.

Alexander developed an extremely effective technique to free us from the cycle of stimulus and habitual response allowing the possibility for change on a deep level. Through the technique one can learn to let go of the things holding us back from reaching our full potential. F.M. Alexander was a Shakespearian reciter. Fairly early in his career he began losing his voice when he recited. As he only lost his voice when reciting he decided that something he was doing while reciting must have been causing the trouble. He consulted with a physician who agreed with him but could not tell him what he was doing while reciting so he set out find the source of his troubles by using mirrors to observe himself while he recited. F.M. began to notice that when he recited he pulled his head ‘backward and downwards’ onto his spine which in turn was putting pressure on his vocal mechanisms. He concluded that this must be the root of his trouble. What was more, he discovered that this pulling the head into the spine was often the first reaction to the thought of doing any activity.

He also noticed that when he decided to put his head ‘forward and up’ he could not maintain this direction of the head when reciting. He could not feel his habit engaging when we he started to recite, instead he felt as if his head was forward and up when it was in fact being pulled back and down onto his spine. This was a major turning point in his self-exploration because he realized that his feeling sense (proprioception) was not trustworthy. He later realized that he must simultaneously give the intention for each part of the process of the activity while withholding consent to the idea of doing the activity. In other words, if he thought of reciting he would immediately pull his head back and down into his spine because the habitual thought of reciting manifested the habitual coordination associated with the habitual thought.

Alexander came up with an ingenious process to get himself out of the rut he was in. He would give himself the stimulus to do something (such as reciting) but instead of reacting he would say no to any habitual reactions and instead projected the thoughts for “his neck to be free, for his head to go forward and up, his back to lengthen and widen, and his knees to go away” which he came up with as preventative directions against the habits associated with his mis-use patterns. These things happen naturally in someone who has good use. Once he found himself sufficiently well organized by thinking the directions he would either give consent to the activity while simultaneously saying no to his habit and projecting the directions, do nothing, or do some other activity. In this way he slowly restored his childlike use of himself.

We typically haphazardly stumble through the learning processes of life with no idea how to create habits other than the common experience that we must do the task in question “right” many, many times and a habit eventually sets in. At this point we have little conscious control over the habit apart from the ability to initiate (and/or hopefully stop) it. In the dreaded case that one learns a wrong (or bad) habit, common experience is that it is infinitely more difficult to “break” a habit than to create a new one.

Playing the viola is a ridiculously difficult proposition. There are so many things must be going well simultaneously that one simply does not have the conscious bandwidth for all aspects of playing to be directly controlled. Therein lies the need to create a set of habits. Similarly, we do not have the conscious bandwidth to directly control all aspects of balance, breathing, movement, or even thinking, so again we must form habits. The quality of all these habits collectively can be called the habitual use of the self. Charles C. Noble once said, “First we make our habits, then our habits make us.”

The deepest sets of habits are the habits of being: temperament, reactivity, balance, presence & focus, fearfulness, etc. All other habits and functions of the self are affected and built on top of these. Similar to the obvious fact that when one begins playing an instrument the first habits develop and act as a basis for all following habits. Where you hold the instrument determines which bow path is straight, where the fingers and arm are in relation to the torso, etc. It is fairly well known (especially in the viola community) that set-up is important, however little is known about what goes on underneath the instrument. Many positional rules exist, such as holding the instrument parallel to the floor, but what good is that if the person is hunched and pulling all limbs into the torso, or is only able to stand by stiffening the legs and ribs? Where would the viola be if they stopped hunching and unstiffened?

The viola is an inanimate object after all, so what we call viola technique can’t be separated realistically from the technique of movement while balancing in gravity. We are simultaneously moving around the viola, supporting it, and manipulating it. Most people are so bent out of shape by their habits before they ever pick up the viola that telling them, release this, raise your elbow, or whatever specific instruction that seems appropriate only layers on more habits to the onion of habits they’ve already created.

The viola is an inanimate object after all, so what we call viola technique can’t be separated realistically from the technique of movement while balancing in gravity. We are simultaneously moving around the viola, supporting it, and manipulating it. Most people are so bent out of shape by their habits before they ever pick up the viola that telling them, release this, raise your elbow, or whatever specific instruction that seems appropriate only layers on more habits to the onion of habits they’ve already created.

This is not to say that new habits layered on top of a mess can’t be helpful, at least temporarily. Instead my point is that we can use the Alexander Technique as a shortcut to something more substantial; to cut right to the core of our being and to break the cycle of reacting and doing in the old way. This is the starting point to play like Primrose, to be a natural. The old pathways will always be there and will be tempting, but to get where you want to go you must take a new path, there is no way to get new ends with old means.

The Alexander Technique by Judith Leibowitz & Bill Connington opens, not with a technical definition or theoretical/philosophical description as many books on the Alexander technique do, instead the authors choose to begin with a relatable list of a variety of imaginary people with stress related ailments asking the reader what they have in common followed by a very straightforward explanation that excess tension and stress are direct results of misuse of the body. They even go so far as to list a number of conditions that can be alleviated by using the Alexander Technique.

The Alexander Technique by Judith Leibowitz & Bill Connington opens, not with a technical definition or theoretical/philosophical description as many books on the Alexander technique do, instead the authors choose to begin with a relatable list of a variety of imaginary people with stress related ailments asking the reader what they have in common followed by a very straightforward explanation that excess tension and stress are direct results of misuse of the body. They even go so far as to list a number of conditions that can be alleviated by using the Alexander Technique. Body Learning by Michael J. Gelb was one of the first texts I read on the Alexander Technique, as it was required reading in the very first group introduction to the AT class I took. Upon re-reading it I see now why my teacher and so many others recommend the book to people with little or no experience with the AT. The book contains all of the core concepts of the Alexander Technique with minimal pontificating on possibilities of the future of mankind and other dense topics that plague many AT books, including ones written to be introductions. Also somewhat important in an introduction to the Alexander technique, which can sometimes be seen as a strange and esoteric practice, is the fact that Michael Gelb carriers some weight as an author from his other books which lends itself to the AT; not to mention the many endorsements by well-known individuals in related fields and a foreword by Walter Carrington.

Body Learning by Michael J. Gelb was one of the first texts I read on the Alexander Technique, as it was required reading in the very first group introduction to the AT class I took. Upon re-reading it I see now why my teacher and so many others recommend the book to people with little or no experience with the AT. The book contains all of the core concepts of the Alexander Technique with minimal pontificating on possibilities of the future of mankind and other dense topics that plague many AT books, including ones written to be introductions. Also somewhat important in an introduction to the Alexander technique, which can sometimes be seen as a strange and esoteric practice, is the fact that Michael Gelb carriers some weight as an author from his other books which lends itself to the AT; not to mention the many endorsements by well-known individuals in related fields and a foreword by Walter Carrington. Having had a fair amount of personal experience with John Nicholls in lessons and classes, I had some preconceived ideas about how this book would read. I expected a straight-forward pseudo-medical explanation with scientific research to support the ideas without the “hippie stuff” that comes with many of his generation’s group of teachers. I was surprised that within the first chapter the conversation had already included Buddhist meditation, Gurdjieff, and possibilities for world change as a result of AT work. The subject of morality came up as John Dewey, Dr. Frank Pierce Jones, and Aldous Huxley believed that the technique lead to a form of ethics/morality. John Nicholls inferred that, “[the AT] may help the construction of a personal morality out of one’s own experience;” that the AT helps “to connect with the inner guide.” JN drew connections through many seemingly unrelated areas; he pointed out an interesting parallel to the schooling of horses, noting that the idea of “Self-carriage” or support of the limbs by the back is very similar to the idea of Primary Control. All of the subjects were approached and discussed in very practical ways without making any far reaching claims lacking evidence.

Having had a fair amount of personal experience with John Nicholls in lessons and classes, I had some preconceived ideas about how this book would read. I expected a straight-forward pseudo-medical explanation with scientific research to support the ideas without the “hippie stuff” that comes with many of his generation’s group of teachers. I was surprised that within the first chapter the conversation had already included Buddhist meditation, Gurdjieff, and possibilities for world change as a result of AT work. The subject of morality came up as John Dewey, Dr. Frank Pierce Jones, and Aldous Huxley believed that the technique lead to a form of ethics/morality. John Nicholls inferred that, “[the AT] may help the construction of a personal morality out of one’s own experience;” that the AT helps “to connect with the inner guide.” JN drew connections through many seemingly unrelated areas; he pointed out an interesting parallel to the schooling of horses, noting that the idea of “Self-carriage” or support of the limbs by the back is very similar to the idea of Primary Control. All of the subjects were approached and discussed in very practical ways without making any far reaching claims lacking evidence.